Chapter 1: Introduction

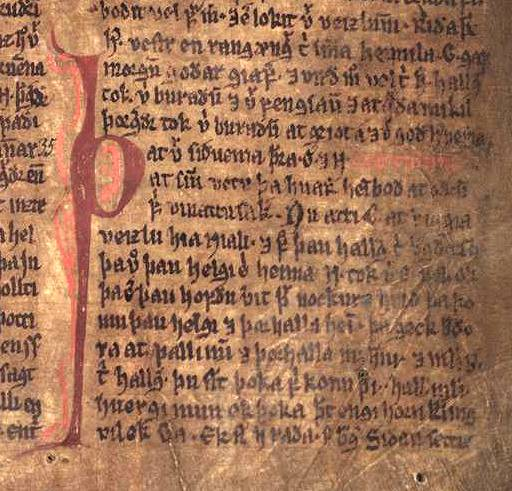

A medieval manuscript page (folio 13r of Möðruvallabók) containing part of Njál’s saga. The Sagas of Icelanders were preserved in such manuscripts from the 13th century onward.

The Icelandic Family Sagas (Íslendingasögur) are medieval prose narratives that recount the lives, feuds, and adventures of notable Icelandic families in the 9th–11th centuries. They were written down in the 13th century, primarily in Old Norse, and form the centerpiece of Iceland’s literary heritage. Unlike medieval tales of knights or kings, these sagas focus on farmers, chieftains, and their kin, portraying a pioneering society in early Iceland. They are a unique contribution to Western literature – often considered Europe’s first novels – renowned for their realism, sparse yet powerful style, and deep insight into human nature. Composed in the vernacular language, the sagas combine history and fiction into unified narratives that feel both authentic and dramatically compelling.

From about 930 to 1030 – the era of the Icelandic Commonwealth – the events of the family sagas unfold against a backdrop of a law-governed, yet often violent, society on the margins of Europe. The sagas were written hundreds of years later, so their exact authorship and historical accuracy are uncertain and have long been debated. Some scholars argue that individual 13th-century writers crafted them as historical novels, while others suggest they grew out of oral traditions passed down through generations. Regardless of origin, the sagas carry a truth of their own: they vividly capture the “grim ethos of a vanished way of life”, portraying it with dramatic power and laconic eloquence. Readers encounter a world governed by honour and vengeance, where minor slights can spiral into deadly feuds, and where strong characters meet their fate with stoic courage.

Culturally, the Sagas of Icelanders have been fundamental to Icelandic identity. They have been described as “the foundation of Icelandic culture, [having] forged the nation’s identity and inspired people to bold deeds in times of adversity”. These stories of ancestors settling a harsh land and upholding their honour helped later generations of Icelanders understand their roots. Even today, the sagas remain an intrinsic part of Iceland’s cultural consciousness. In 2009, the entire medieval manuscript collection of Árni Magnússon – which preserves many of the sagas – was inscribed on UNESCO’s Memory of the World Register, underscoring their global significance. The sagas’ influence reaches far beyond Iceland: they have inspired writers and artists worldwide, including luminaries like William Morris, J. R. R. Tolkien, and Jorge Luis Borges. These fans have admired the sagas’ narrative artistry and the window they provide into the Viking Age.

Literarily, the family sagas are celebrated for their austere yet gripping style. The prose is plain and unadorned, with careful use of understatement and irony. Adjectives are used sparingly; instead, character is revealed through action and especially through dialogue. This restraint gives the sagas a feeling of objectivity and realism – the authors seldom explicitly judge their characters, allowing deeds and words to speak for themselves. Yet within this sparse style, the sagas achieve intense emotional impact and “overwhelming tragic dignity”. The best sagas draw the reader into profound dramas of fate, where proud men and women contend with family loyalties, honour, love, and revenge. Common themes include the bonds and conflicts of kinship, the demands of honour, the cycles of blood feud and the hope for reconciliation, the clash between pagan honour codes and the arriving new faith of Christianity, and the struggles of individuals against their fate. Despite being written in a distant era, these stories deal with timeless human problems – broken friendships, vengeance and justice, the grief of loss, and the search for peace.

There are around 40 extant family sagas, anonymous works penned by unknown Icelanders. Among these, a few stand out as masterpieces for their length, complexity, and literary quality. Brennu-Njáls saga (Njál’s Saga), Egil’s saga, and Gísla saga are three of the most famous examples. Njál’s saga in particular is often hailed as the greatest of all – the peak of the saga tradition in its narrative scope and depth of characterization. In the chapters that follow, we will explore these three sagas in detail. Each chapter will present an engaging retelling of the saga’s story – bringing to life its heroes, villains, and dramatic turns – and then discuss the saga’s key themes, motifs, and structure. Through these tales of Gunnar and Njáll, of Egil Skallagrímsson, and of Gísli Súrsson, we gain insight not only into medieval Iceland, but into universal human sagas of friendship, betrayal, endurance, and destiny.

Chapter 2: Brennu-Njáls saga – The Saga of Burnt Njáll

The Story of Njáll and Gunnar

Njál’s Saga opens in 10th-century Iceland, introducing us to two close friends whose fates will become tragically intertwined. Njáll Þorgeirsson of Bergþórshvoll is a wise chieftain and skilled lawyer, respected for his judgment and foresight. His dearest friend is Gunnar Hámundarson of Hlíðarendi, a handsome and peerless warrior, unrivaled in arms and athletic prowess. Though coming from different regions (Njáll from the south, Gunnar from the west), the two men form a bond of brotherhood. Njáll’s calm wisdom complements Gunnar’s bold courage, and for a time they prosper – ideal figures of sage and hero – in a land still ruled by honour and law. But the saga foreshadows that even the greatest of men cannot escape the entanglements of feud and fate.

Gunnar’s life takes a fateful turn when he meets the beautiful Hallgerður Höskuldsdóttir. Hallgerður – tall, striking, with “thief’s eyes” – has already been twice widowed under dark circumstances. Despite Njáll’s subtle warnings about her character, Gunnar falls in love and marries Hallgerður. The marriage links Gunnar’s fortunes to Hallgerður’s volatile pride, and soon conflicts arise. Meanwhile, Njáll is married to the strong-willed Bergþóra, and the two couples (Njáll with Bergþóra, Gunnar with Hallgerður) become friends. At communal feasts they honour each other – yet tension simmers beneath the surface, especially between the wives. A deadly insult sets events in motion: Bergþóra and Hallgerður quarrel, each vowing not to be outdone. What begins as a household squabble escalates into a series of tit-for-tat killings. Hallgerður instructs one of her servants to kill a man in Njáll’s household over a trivial affront; in retaliation, Bergþóra has one of her kinsmen slay a follower of Hallgerður. Back and forth the revenge goes, claiming beloved kinsmen on both sides. Through it all, Njáll and Gunnar strive to remain friends and patch up the feuds with settlements of compensation. Their friendship holds strong – Gunnar even says he would never break with Njáll, “however it might go between our wives.” Thanks to Njáll’s wisdom and Gunnar’s honour, several peacemakings are achieved, and for a while a fragile calm persists.

However, new troubles are fermented by a scheming figure, Mörðr Valgarðsson, who envies Gunnar. Mörðr fans the flames of resentment among those who have paid blood-prices in the settlements. Eventually he goads a group of Gunnar’s enemies into attacking him, breaking the peace. Gunnar, the indomitable fighter, fends off the attackers and wins the battle. But in the fray, he unwittingly kills twice within the same family – a grave violation of the accepted norms. Njáll, who has the gift of foresight, had prophesied that if Gunnar ever committed such an act and then broke the terms of settlement, it would lead to his doom. And indeed, after this fight Gunnar is formally declared an outlaw by the Althing (Iceland’s national assembly). The law calls for Gunnar to be exiled from Iceland for three years as punishment.

At first, Gunnar means to obey the law. He prepares a ship to depart Iceland with his brother Kolskeggur. But as Gunnar rides away from his home at Hlíðarendi, he pauses on a hillside. Gazing back at his beloved farm in the sunlight, he is overcome with longing. “How fair is my home, the fields green and beautiful – I will not go,” he declares. Despite the sentence of outlawry, Gunnar’s attachment to his land is so strong that he decides to stay in Iceland illegally. This poignant moment seals Gunnar’s fate. Once word spreads that Gunnar has defied the exile, his enemies are emboldened to seek vengeance openly.

Before long, a band of Gunnar’s foes gathers to assault him at Hlíðarendi. Gunnar, though now essentially alone, makes a legendary last stand. He is said to have fought off around thirty men single-handedly, shooting arrows with deadly accuracy. According to the saga, he wields his great bow until the weapon’s bowstring is cut. Desperate for something to restring the bow, Gunnar asks Hallgerður for strands of her long hair. In a chilling moment, Hallgerður refuses – she reminds Gunnar of the time he slapped her, and coldly says, “I shall now repay that blow.” Thus denied, Gunnar is left with no working bow. He fights on with sword and spear, killing two more attackers, but the odds are too great. The enemies dare not enter the house to face him man-to-man – instead, at Mörðr’s urging (though some call it shameful), they climb onto the roof and tear it off to get at Gunnar. Surrounded and weapon-less, Gunnar falls, pierced by spears. His death is the first great tragedy of the saga. Gunnar dies in his home, undefeated in open combat – betrayed by fate and by Hallgerður’s vengeful pride. When Njáll hears of his friend’s end, he recites a verse honouring Gunnar and says there will never be a better man in all of Iceland.

After Gunnar’s fall, Njáll becomes the central figure. He takes Gunnar’s young son Högni into his care and helps arrange vengeance against some of Gunnar’s killers, but Njáll mostly counsels patience and lawful redress. Time passes, and Iceland converts to Christianity around the year 999, an event briefly noted in the saga. Njáll himself, known as “the beardless” and sometimes taunted for his lack of manly beard, remains a voice of wisdom and piety in this changing world. He and Bergþóra have grown sons, notably the fierce Skarp-Héðinn Njálsson, a formidable warrior with a sharp tongue, and Höskuldur (Hoskuld) whom Njáll fosters as a surrogate son. Njáll’s family is drawn into new conflicts when a relative, Þráinn Sigfússon (a man allied by marriage to Hallgerður), provokes them. Skarp-Héðinn and his brothers ambush Þráinn in a dramatic encounter on a frozen river – Skarp-Héðinn slides on the ice and with one swing of his axe splits Þráinn’s skull, an iconic moment of Njál’s saga’s action. Though this feud is settled by arbitration, it leaves lasting grudges. Njáll, hoping to avert further bloodshed, adopts the orphaned Höskuld Þráinsson and raises him lovingly. Njáll even helps Höskuld attain chieftain status and arrange a marriage, trying to secure a peaceful future.

Tragically, Njáll’s efforts to prevent violence come undone. The scheming Mörðr Valgarðsson, the same instigator of Gunnar’s demise, now turns his envy toward the successful young chieftain Höskuld (Njáll’s foster-son). Mörðr whispers to Njáll’s sons that Höskuld stands in their way. Although Njáll’s sons know it is wrong, they are “so susceptible to his promptings” that one day, along with Mörðr and Kári (Njáll’s son-in-law), they ambush and murder Höskuld while he is sowing grain in his field. It is a senseless killing of an innocent man – the saga laments that Höskuld was “killed for less than no reason; all men mourn his death; but none more than Njáll, his foster-father”. Njáll is heartbroken that his own kin have committed such a crime. This slaying is the final catalyst for the saga’s most devastating chain of vengeance.

Höskuld’s kinsman and patron, Flosi Þórðarson, swears blood-revenge on the killers. Flosi gathers a formidable alliance of chieftains from across Iceland to demand justice. The stage is set for a colossal confrontation at the Althing, the national court, where Njáll’s sons must answer for their deed. That summer at Thingvellir, the legal proceedings turn into high drama. Njáll’s side, led by his foster-son Þórhall (who is a lawyer Njáll trained, though he arrives injured and limping), try to prosecute the case, while Flosi has bribed a top lawyer to defend his side. After complex legal wrangling, a settlement is nearly reached: wise men propose that Njáll’s side pay a massive compensation (a triple wergild) for Höskuld’s death. So much silver is gathered from all supporters that it amounts to an unprecedented sum – Njáll even adds a fine cloak to the offer. It seems peace might yet prevail. But at the moment of settlement, Flosi feels insulted by a jibe from Skarp-Héðinn and by the gift of Njáll’s cloak (which he calls a “woman’s garment”). Enraged, Flosi rejects the settlement and stalks away, declaring there will be no blood-price accepted for Höskuld. The fragile truce shatters. Fighting erupts at the Althing; weapons clash and men fall until leaders intervene to stop the brawl. Ultimately, with trust broken, the rule of law fails to resolve the feud.

After the Althing, Flosi and his coalition resolve to take vengeance directly on Njáll and his clan. Njáll, old but unyielding, seems to sense what is coming. One night he tells his family of dark portents he has seen, predicting that their home will be attacked. Rather than flee, the proud Njáll chooses to face fate head-on. Sure enough, one night a band of a hundred men led by Flosi descends upon Bergþórshvoll, Njáll’s homestead. Njáll’s sons and a few loyal friends arm themselves and bar the doors. Outnumbered five-to-one, they still manage to kill several attackers in the initial skirmish. But Flosi’s men then resort to the dreaded tactic that gives the saga its name. They surround the house and set it ablaze. As flames engulf the building, Flosi calls out that any women inside may leave unharmed. Njáll’s wife Bergþóra refuses to abandon her husband; she stays by Njáll’s side. Flosi even offers to let Njáll himself come out, due to respect for his age and wisdom. But Njáll, with quiet dignity, answers that he will not outlive his sons. Choosing loyalty in death, Njáll and Bergþóra sit together with their grandson in the burning house, calmly awaiting the end. They, along with Njáll’s sons and other household members, perish in the inferno. Only one important figure escapes: Njáll’s son-in-law Kári Sölmundarson makes a daring dash through the smoke and, miraculously, evades the attackers. Kári flees into the night, grieving yet determined on revenge. The charred ruins of Bergþórshvoll become a somber symbol of how far the cycle of vengeance has gone – virtuous Njáll, who always sought peace, has been martyred in the flames of feud.

Even after this cataclysm, the saga continues to narrate the aftermath of Njáll’s burning. At the next Althing, with emotions at a fever pitch, the two sides prepare for battle on the Law Rock itself. In a remarkable legal showdown, the case of the burners of Njáll’s home is brought to court. When procedural tricks threaten to derail justice, open combat breaks out at the Althing – essentially a small civil war among the assembled clans. Weapons clash in the very site dedicated to law, until eventually the carnage is halted by mutual friends. At last, an elderly chieftain gains everyone’s attention and pleads for peace, reminding them that continuing the bloodshed will only destroy their society. Moved by this, most of those present agree to negotiate. A settlement is reached: Flosi and his men (the burners) will pay heavy fines for the death of Njáll’s family, and in return they will be exiled from Iceland. Astonishingly, nearly all accept this resolution – a moment of reconciliation after so much strife. Only Kári and one other refuse to be satisfied; Kári remains intent on personal vengeance and does not accept the blood-money.

The saga’s final chapters follow Kári’s pursuit of the burners across the sea. Kári tracks them down one by one, demonstrating the relentless persistence of the old honour code. Some he catches in Orkney, killing a couple of Flosi’s comrades in a hall burning (a grimly fitting fate). Eventually, however, even fiery Kári finds closure. Flosi, after years abroad, goes on a pilgrimage to Rome seeking absolution. By chance, Kári is on the same ship returning to Iceland. When a shipwreck nearly kills Kári near Flosi’s new home, Flosi magnanimously rescues him. The two former enemies then meet, not as warrior and prey but as respectful men who have both suffered great losses. In a moving conclusion, Kári accepts Flosi’s hospitality and they make peace. Kári even marries Flosi’s niece (the widow of Höskuld) and thus ties the two families together, healing the wounds at last. The saga ends with this reconciliation, suggesting a hopeful resolution: the cycle of vengeance is broken, and some measure of peace and renewal is achieved after the tragedy.

Thus, Brennu-Njáls saga spans the lives of its protagonists from prosperity to ruin, against the wider social changes in Iceland (including the coming of Christianity and the evolving legal system). It is a rich tapestry of heroism and heartbreak – Gunnar’s unmatched bravery, Hallgerður’s prideful spite, Njáll’s steadfast wisdom, Skarp-Héðinn’s fierce humor, Flosi’s grim resolve, and Kári’s eventual mercy all stand out as unforgettable parts of the story. With its sweeping scope and profound characters, Njál’s saga earns its reputation as one of the most powerful sagas of the Icelanders.

Themes and Analysis

Brennu-Njáls saga is widely regarded as a masterpiece for its complex exploration of law, honour, and fate in a society on the cusp of change. One of its central themes is the destructive cycle of blood-feuds and the attempts to replace vengeance with justice. The saga graphically illustrates how an insult or minor incident – often stemming from a point of honour – can spiral into a long chain of killings spanning decades. We see this with the feud between Hallgerður and Bergþóra, and later in the fatal quarrel over Höskuld’s murder. The saga does not shy away from depicting the tragic cost: families are eradicated and beloved friends turn to ashes. Through these stories, Njál’s saga conveys the idea that a strict honour code, where any slight must be avenged in blood, creates a self-perpetuating tragedy for society.

Yet, running counter to the violence is the saga’s ideal of law and justice. Njáll himself embodies the belief in law as a better path. He is a skilled lawyer and repeatedly urges legal settlements over revenge killings. The Althing scenes – especially the settlement offer for Höskuld’s death – highlight the medieval Icelandic legal system’s effort to control violence through compensation and arbitration. When those efforts fail (as with Flosi’s rejection of the settlement), the saga shows the grave consequences: the lawgiving assembly dissolves into chaos and fighting. In this way, Njál’s saga dramatizes a struggle between law and vengeance, reflecting the saga author’s awareness of how fragile the rule of law can be in the face of honour-bound men. The eventual reconciliation between Kári and Flosi suggests hope that personal forgiveness can succeed where formal resolutions did not.

Another theme is the role of fate and omens. The saga is filled with prophetic dreams, visions, and wise sayings that foreshadow events. Njáll predicts Gunnar’s downfall if he breaks his settlement; the seeress predicts discord among the friends in Hlíðarendi; characters have dreams of their own deaths. These supernatural or premonitory elements contribute to a fatalistic tone. Often the characters seem unable to escape what destiny has laid out – for instance, despite all Njáll’s wisdom and Gunnar’s prowess, they move steadily toward tragedy as if fate had ordained it. The presence of omens and dreams also underscores a transitional period between the pagan past and a Christian worldview. Notably, the saga’s central section includes the Conversion of Iceland to Christianity (in the year 1000) as a backdrop. While the saga’s heroes and villains are mostly pagan (since the events occur just before and after the conversion), the author – likely writing as a Christian – may subtly frame Njáll (who converts and is portrayed almost like a saintly figure accepting martyrdom in fire) as a Christ-like contrast to the “bad pagan” ethos of endless revenge. Indeed, one interpretation is that Njáll’s death in the flames, refusing to escape, is like a martyr’s death, representing the idea that goodness can transcend the violent world around it.

The saga also richly explores character and ethics through its cast. Friendship and loyalty are celebrated – the bond between Njáll and Gunnar is depicted as deep and exemplary. Their friendship endures all tests until Gunnar’s death, showing an ideal of steadfast loyalty. Honour is a double-edged concept in the saga: on one hand, virtues like courage, generosity, and keeping one’s word are praised (Gunnar and Njáll are admired for these traits). On the other hand, a misplaced sense of honour (often tied to masculinity and pride) leads to disaster. For example, Hallgerður’s refusal to help Gunnar with the bowstring – because she cannot forgive a past insult – is a poignant example of pride undoing the very person she should support. The saga pointedly examines gender and honour, as well: women like Hallgerður and Bergþóra instigate and perpetuate feuds, challenging the men’s attempts at peace. It’s notable that one scholarly view sees the saga as subtly criticizing a misogynistic society – many male characters’ sense of manhood is easily wounded, and the saga may be suggesting that this obsession with macho honour is ultimately ruinous. The presence of strong female figures who drive the action (for better or worse) also gives the saga much of its dramatic tension.

Structurally, Njál’s saga is admired for its unity and narrative sophistication. It is one of the longest sagas, yet the author maintains tight control over multiple interweaving plotlines. The saga is often divided into key movements: the rise and fall of Gunnar, the building feud leading to the Burning, and the revenge of Kári. Despite the many characters and episodes, the saga continually circles back to its central themes of friendship and feud, law and chaos. Critics have noted the artistic unity in how events are foreshadowed and mirrored: for instance, Gunnar’s heroic last stand foreshadows Njáll’s own end; the initial house-burning committed by Njáll’s family (against enemies, earlier in the saga) is grimly echoed by the burning of Njáll’s house. There is even a sense of poetic justice or irony in many episodes – such as the way Gunnar’s fate is sealed by the very woman he married, or how Flosi, who burned Njáll’s family, later becomes the instrument of saving Njáll’s avenger Kári, enabling closure.

Finally, the saga’s literary style deserves comment. Njál’s saga exemplifies the saga style at its height: the narration is dry and unemotional even when describing the most horrific or poignant events. This understatement forces the reader to read between the lines and often heightens the impact. Dialogue is a key vehicle for meaning – many of the saga’s famous lines (like Gunnar’s last words about the beauty of his home, or Skarp-Héðinn’s biting insults) reveal character and carry thematic weight. After major deaths, the saga often gives a valedictory speech or a poetic verse in the voice of the dying or their loved ones, allowing a moment of reflection. For example, Skarp-Héðinn’s dark humour till the end, or Njáll’s calm acceptance in the fire, leave strong impressions. The saga writer’s skill is evident in how scenes are set and how tension is built – from legal drama in the courtroom to action on the battlefield to intimate domestic confrontations. It is little wonder that Njál’s saga is regarded as the culmination of the saga genre, a work that combines social commentary with epic tragedy, all while keeping readers gripped by its narrative momentum.

In summary, Brennu-Njáls saga is not only a compelling story of friendship and vengeance in Viking-age Iceland; it is also a profound meditation on the transition from an old world of honour-bound blood feuds to a new order of law and Christian ethics. General readers admire it for its memorable characters and dramatic storytelling, while scholars continue to mine its depths for insight into medieval mentality and narrative art. It stands as a towering achievement among Icelandic family sagas – an enduring saga of a society trying to find justice amid chaos, and of noble individuals caught in the cruel workings of fate.

Chapter 3: Egils saga – The Saga of Egil Skallagrímsson

The Viking Poet’s Journey: The Story of Egil

Egill Skallagrímsson depicted in a 17th-century manuscript of Egils saga. Egil was as famed for his prowess in battle as for his gift in poetry, embodying the saga’s blend of the warrior and the skald.

Egils saga (the Saga of Egil) plunges us into a sprawling Viking epic that spans roughly 150 years, from about 850 to 1000 AD. It is both a family chronicle and the personal story of one of Iceland’s most larger-than-life figures: Egill Skallagrímsson. Egil is portrayed as a fierce warrior, a clever adventurer, and one of the greatest poets (skalds) of the Viking world. His saga is rich with battles, voyages, duels of wits, and a wealth of poetry composed by Egil himself. Through Egil’s long and tumultuous life, the saga explores the fortunes of a family caught between the independence of Iceland and the royal power struggles of Norway.

The story begins a generation before Egil’s birth, in Norway. Egil’s grandfather, Úlfr (nicknamed Kveld-Úlfr or “Evening-Wolf”), is a mighty chieftain known for his prodigious strength and strange fits of ferocity at nightfall – hints of a shape-shifting berserker nature that will reappear in his descendants. Kveld-Úlfr’s refusal to serve King Harald Fairhair (the monarch unifying Norway) sets in motion a family rift with the Norwegian crown. Kveld-Úlfr’s elder son, Þórólfr (Thorolf), becomes a dashing warrior in King Harald’s court. But through court intrigues, Thorolf falls out of favour and is killed by the king’s men. The surviving brother, Skalla-Grímr Kveldúlfsson (Egil’s father), decides to flee Norway to escape Harald’s wrath. Kveld-Úlfr and Skalla-Grímr lead their family and followers across the sea to a new frontier – Iceland – during the great era of settlement around 900 AD. They claim land in Borgarfjörður in west Iceland, establishing a farm and a new lineage far from the reach of kings.

It is in Iceland that Egill Skallagrímsson is born (around 910 AD, according to saga chronology). From childhood, Egil shows extraordinary traits – both good and bad. As a bald-headed little boy of 3, he composes his first poem, astonishing his family by his precocious wit. Yet Egil also has a dark, violent streak. At the age of 7, insulted during a ball game, young Egil flies into a rage and kills an older boy with an axe. This shocking deed is recounted matter-of-factly in the saga, marking Egil early on as someone who embodies the uncontrolled ferocity of his grandfather’s “Evening-Wolf” spirit. Egil grows up ugly and blunt-spoken, but immensely strong and fearless. He hero-worships his older brother Thorolf (named after their late uncle), who is everything Egil is not: handsome, even-tempered, and favoured by all. The bond (and occasional rivalry) between Egil and Thorolf is a running thread in the saga, showing Egil’s capacity for deep loyalty alongside his capacity for violence.

As a young man, Egil cannot be contained by peaceful farming life. He and Thorolf set off on Viking voyages, seeking adventure and fortune overseas. They journey through the Baltic and Scandinavia, raiding and feasting as was the custom for bold Icelandic youths. Eventually, they enter the service of King Athelstan of England. In one celebrated episode, Egil and Thorolf fight as mercenaries for Athelstan at the Battle of Brunanburh (circa 937), where Egil’s ferocity in battle contributes to Athelstan’s victory over his enemies. The saga includes verses attributed to Egil about this battle, placing him in the grand historical context of Norse warrior-poets who traveled widely.

Egil’s most fateful adventures, however, involve the royalty of Norway. After King Harald Fairhair’s death, his son Eiríkr Bloodaxe and Queen Gunnhildr come to power. Egil’s family has a long-standing feud with these royals (since Harald and his kin killed Egil’s uncle Thorolf long ago). Initially, Egil tries to avoid conflict – he even becomes close friends with Arinbjǫrn (Arinbjorn), a nobleman in Norway and a friend of Egil’s who serves King Eiríkr. But trouble finds Egil. During a stay at Eiríkr’s court, Egil gets into a lethal quarrel with Bárðr, one of the king’s men, over an issue of hospitality and insults. Egil ends up killing Bárðr at a feast. This enrages King Eiríkr and especially Queen Gunnhildr, who from that moment hate Egil bitterly. Egil is forced to flee Norway as an outlaw, with the royal couple vowing to have his head.

Thus begins Egil’s personal vendetta against King Eiríkr and Queen Gunnhild. Egil retaliates in dramatic Viking fashion: when one of Eiríkr’s sons, Rǫgnvaldr, happens to be in England fighting for Athelstan, Egil faces Rǫgnvaldr in battle and slays him. In a symbolic act of defiance, Egil then goes to Eiríksstaðir (the Norwegian king’s farmstead in Norway), and erects a níðstǫng – a pole of curse, topped with a horse’s head – declaring he is raising a curse to drive King Eiríkr and Queen Gunnhild from the land. This vivid scene (the curse pole facing the winds) underscores Egil’s role as a daring opponent of tyranny, unafraid to use both violence and magic-tinged ritual to make his point.

Eiríkr and Gunnhild are furious and put a bounty on Egil. Eventually, Egil is captured by King Eiríkr’s men and faces execution – leading to one of the saga’s most famous moments. Egil is held prisoner overnight, expecting to be killed in the morning. Instead of despairing, Egil calls upon his gift for poetry. In the span of one night, he composes a long praise-poem honouring King Eiríkr, known as “Höfuðlausn” (Head-Ransom). At dawn, Egil recites this poem before the king. The verses are so skilfully wrought and so lavish in praising Eiríkr’s bravery that the king’s anger is appeased. In a remarkable turnabout, Eiríkr spares Egil’s life and even rewards him. This incident – a poet literally winning his freedom with words – has become legendary in Icelandic literature, exemplifying the high value placed on poetry. It shows Egil’s cunning and the power of art to overcome violence. Queen Gunnhild, however, is not placated; she continues to plot Egil’s destruction with implacable hatred.

After this narrow escape, Egil returns to Iceland for a time, bringing with him wealth and honour gained abroad. He settles down enough to marry Ásgerðr (Asgerd), who happens to be the daughter of his beloved friend (and blood-brother) Thorolf and also – in a twist of saga genealogy – the widow of Björn, a man Egil killed in an earlier feud. Through Asgerd, Egil later becomes entangled in a inheritance dispute back in Norway. Asgerd’s father, a wealthy man, had property that fell under the control of King Hákon (another son of Harald Fairhair who ruled after Eiríkr was deposed). When Asgerd’s share of this inheritance is withheld, Egil sails to Norway to claim it. King Hákon (though more just than Eiríkr) is reluctant to anger powerful locals who hold the property, so Egil must fight and outwit a figure named Ármóðr and others to get what is owed. Egil eventually succeeds by a mix of legal shrewdness and intimidation – even almost coming to blows with King Hákon’s men – but secures Asgerd’s inheritance. This episode underscores a recurring motif: Egil constantly navigates the tension between proud, independent Icelanders like himself and the authority of Norwegian kings. Egil respects fair rule but bristles at any attempt to cheat or control him.

Throughout Egil’s saga, we see Egil’s character in all its complexity. He can be wild, cruel, and impulsive – as in his youthful killings or when he commits massacres in battle. Yet he is also shown as capable of great loyalty and deep feeling. His devotion to his friends and family is fierce. When his dear brother Thorolf is killed in battle, Egil is inconsolable and vows to avenge him, which he does by slaying the responsible Scottish earl. Egil’s best friend, Arinbjorn, stands by him in dire situations, and Egil composes heartfelt verse praising Arinbjorn’s loyalty. Indeed, Egil’s poetry is a window into a soul far more sensitive than one might expect from a blood-stained Viking. His verses praise friendship, lament loss, and even muse on the fleeting nature of life.

One of the saga’s most moving passages comes in Egil’s old age. Back in Iceland, having survived into his seventies, Egil faces the hardest blow of his life: the death of his beloved son Bǫðvarr (Bodvar) in a drowning accident. The once-indomitable Egil is plunged into despair. He becomes bedridden with grief, refusing to eat or speak. Finally, drawing on his poetry one last time, Egil composes a profound elegy called “Sonatorrek” (“Loss of Sons”). In this long poem (which the saga presents as Egil’s own composition), Egil expresses the fathomless pain of a father outliving his children, likening his grief to a storm-tossed tree that has lost its branches. He also reflects on the inevitability of death and even offers a bittersweet reconciliation with the gods – acknowledging Odin, patron of poets, who gave him the gift of verse but also took away his son. Writing this lament pulls Egil from the brink of suicide. It stands as one of the great poetic accomplishments within any saga, showing Egil as not just a warrior brute but a man of introspective depth and emotional vulnerability.

After this, Egil’s saga winds down. Nearly blind and feeling his strength waning, Egil arranges his last affairs. There’s a grimly humorous anecdote of Egil hiding his treasure: angry at the locals and the idea of anyone unworthy inheriting his wealth, Egil buries a chest of silver (loot from earlier raids) somewhere in the region, and its location is lost – a bit of Viking pirate lore about hidden treasure. Egil dies in Iceland, reportedly so large in stature that when his bones are later exhumed, his skull is immensely thick (legend says a blade could not pierce it). Thus ends Egil’s life story, but the saga also notes his lineage: Egil’s descendants, through a daughter, include future notable Icelanders (and it is often theorized that the saga’s author may have been among them, possibly Snorri Sturluson, who was thought to be a descendant of Egil’s family).

In Egils saga, the wide-ranging adventures – from Norway to England to Saxony to Iceland – and the intermix of historical personages (kings like Athelstan and Eiríkr) give the tale an almost legendary scale. Yet it stays grounded in the very human figure of Egil, who is by no means an unblemished hero. He can be seen at times as an anti-hero: he murders rashly, he’s often motivated by greed or anger, and he is described as physically ugly, with a bullying temper. But the genius of the saga is that by the end, readers often sympathize with Egil, having witnessed his loyalty, his love for kin, his suffering, and his creative spirit.

Themes and Analysis

At its core, Egils saga is a portrait of a complex individual and the turbulent world he inhabits. One key theme of the saga is the duality of Egil’s character – the warrior and the poet, the “dark” Viking and the deeply human soul. Egil embodies the rough virtues and vices of the Viking Age more than perhaps any other saga hero. On one hand, he is violent, vengeful, and fiercely independent; on the other, he is capable of introspection, abiding friendships, and sublime artistic expression. The saga uses Egil’s own poetry (with over 60 verses attributed to him) to illuminate his inner life. Through those verses, we glimpse Egil’s sorrow at deaths of loved ones, his pride in victories, and his capacity to praise or curse with equal skill. The poems “speak to universal themes of friendship, death, and old age,” making Egil’s Viking world feel authentic and relatable to readers. This interplay of action and poetry suggests that, to the saga author, Egil’s legacy as a poet is just as important as his deeds as a warrior – if not more so. It’s Egil’s verses that “eternalize the heritage he shares with his countrymen” and give voice to values and emotions that resonate beyond his own story.

Another major theme is the clash between the Icelandic free spirit and the power of kingship. Egil’s family’s troubles begin with conflict against King Harald Fairhair’s unification of Norway. Throughout the saga, Egil and his kin stand somewhat in opposition to Norwegian royal authority. Egil’s personal feud with King Eiríkr Bloodaxe and Queen Gunnhild dramatizes this tension. In one analysis, a “major theme of Egils saga…is relations between the Norwegian kingship and the Icelandic commonwealth.” Egil is proud of his Icelandic identity – he comes from a land with no king, where chieftains are semi-independent. His bold acts (like raising the pole of curse against Eiríkr) and his unwillingness to be cowed by royal power reflect a broader Icelandic sentiment of the saga age: a mixture of resentment and defiance towards the concept of monarchy. Yet, Egil is not portrayed as a simplistic rebel; he will cooperate with fair-minded rulers (like Athelstan or even King Hákon to a degree). What Egil (and the saga) cannot abide is unjust or tyrannical behaviour. Thus, Egil’s personal honour code pits him against kings when they violate fairness – such as withholding inheritance or breaking hospitality – showing an Icelandic perspective that loyalty is earned, not owed blindly to a throne. This theme can be read as the saga author’s reflection on the “love/hate relationship with the idea of kingship” among Icelanders.

The saga also deeply explores family loyalty and feud. Egil’s strongest motivations are often familial. He loves his brother Thorolf and avenges him; he cares for his father Skalla-Grímr (despite a fraught relationship – they have a famous wrestling match where Egil is nearly killed by his berserker father’s rage, only their mother’s intervention saves him). Egil also supports and defends his in-laws and children. When his father dies, Egil deals honourably with inheritance (except for the part he hides out of spite – showing even in duty he can be capricious). The saga contrasts Egil’s loyalty with instances of family betrayal or tension – for example, Egil’s own father Skalla-Grímr kills Egil’s friend (and possibly Egil’s foster brother) in a fit of rage during a game; Egil has to manage his anger at his father for that. Also, Egil’s nephew (Thorolf’s son) becomes a Christian, hinting at a generational shift in values by saga’s end. These family dynamics add realistic complexity: Egil’s saga isn’t just war and politics, but also the dramas of home and kin.

A notable structural aspect of Egils saga is how it spans multiple generations – it reads almost like a family saga combined with a hero’s biography. The first part about Egil’s father and grandfather sets up patterns that repeat in Egil’s life (hostility with Norwegian kings, berserker fury, etc.). The saga is carefully structured with recurring motifs, such as the symbolic heirloom sword that appears in Egil’s grandfather’s story and then later (Egil recovers a precious sword from a burial mound in one episode), or the way Egil’s relation with his brother Thorolf mirrors that of his uncle Thorolf and Skalla-Grímr. Scholars have noted subtle structural patterns in the saga that give it coherence despite its episodic nature.

Another theme is the power of art (poetry) versus physical might. Egil’s life constantly balances these two forms of power. He is a fearsome fighter – in some sagas, the hero might rely on strength alone, but Egil stands out because time and again, it is his poetry that achieves what violence cannot. The most obvious case is the “Head-Ransom” poem that saves him from execution. But even beyond that, Egil’s poetry serves as emotional catharsis (the Sonatorrek after his son’s death) and as social capital (his praise of Arinbjorn, or mocking verses that tarnish enemies). Egil’s saga thereby highlights a key cultural value: skaldic poetry was a respected, almost magical skill among the Norse. The saga’s author, by preserving so many of Egil’s supposed compositions, underscores that Egil’s identity as a skald (poet) is as important as his identity as a warrior. The poems themselves enrich the narrative, providing direct insight into Egil’s mind and also demonstrating how cultural memory is kept. Egil’s verse “leads us to view the Saga Age not as an epoch of legend, but as a time as authentic as our own” by expressing genuine human concerns.

In the latter part of the saga, we also see themes of aging and legacy. Egil in old age is a rare depiction in the sagas of a warrior past his prime. We witness Egil’s vulnerability – his physical decline and the emotional devastation of losing his favourite son. The theme of coping with aging and mortality is poignantly handled. Egil’s response is to create: the poem Sonatorrek is his confrontation with mortality. There is also a sense of the end of an era – Egil laments not just his son but also the passing of his generation’s glories. The fact that Egil’s son becomes Christian (baptized when Christianity comes to Iceland) and Egil himself possibly dies a pagan holds symbolic weight: Egil is a figure of the old pagan warrior culture, and after him the world is changing. The saga doesn’t explicitly moralize about this, but it’s implied that Egil’s time was a different, harsher age. Nevertheless, Egil straddles those worlds by leaving behind art that can live on in Christian Iceland.

Literarily, Egils saga is notable for its character study. Egil is not depicted as purely noble or villainous; he’s multifaceted and at times contradictory. Modern readers often find him fascinating precisely because he can be both reprehensible and admirable. The saga author’s achievement is in maintaining a consistent character through so many adventures and years. We see Egil’s temperament from youth to old age, and it feels like the same person growing and changing. Additionally, Egil’s saga has a rich cast of supporting characters (the charming Thorolf, the shrewd Arinbjorn, the malevolent Queen Gunnhild, etc.) who each play roles in testing or highlighting Egil’s qualities. The dialogues in the saga – Egil’s sharp retorts, Gunnhild’s threats, Arinbjorn’s counsel – all serve to flesh out a vibrant social world.

In terms of style, Egils saga combines action-packed episodes with moments of introspection. There are scenes of high adventure: fierce battles at sea, duels on remote islands, ale-fueled feasts with deadly games. These give the saga a fast pace and variety. Interspersed, however, are formal elements like genealogies and legal proceedings (e.g., Egil’s lawsuits over inheritance), grounding the story in the everyday concerns of property and kinship that are typical in sagas. The saga also occasionally injects dry humor – Egil can be darkly funny, like when he kills a man and then composes a flippant verse about the “duck’s egg” shape of the bald head he cut, as a jest. This blending of tones makes Egils saga quite engaging; it isn’t all tragedy or all comedy, but a realistic mixture.

One interesting aspect is the saga’s possible historical intent. It has more connections to recorded history (like mentions of battles known from English sources) than many sagas. The author might have been someone like Snorri Sturluson, an educated chieftain with access to records and poetry, given the saga’s polished narrative and historical scope. There are hints in the text – for example, it acknowledges it’s the “sole source” for Egil’s life and speculates about authorship – suggesting an author consciously preserving history and family lore. Whether historically accurate or not, Egils saga provides a cultural history – showing what values and experiences the saga writer found worth emphasizing: chiefly, the figure of the skaldic warrior as a cultural hero.

In summary, Egils saga is a rich tapestry that explores what it meant to be a formidable individual in the Viking Age. It deals with individualism vs authority (Egil versus kings), the interplay of violent action and creative expression, and the emotional life of a man who could be both a monster and a mourner. For a general reader, Egil’s saga offers an exciting narrative – full of duels, treasure, curses, and narrow escapes – but it also offers a deeply human story of a person navigating loyalty, ambition, and loss. It’s easy to be entertained by Egil’s daring exploits, but equally easy to be moved by his sorrows and to marvel at his poetic genius. The saga thus succeeds on multiple levels, and its enduring popularity comes from this breadth of vision. As one commentator put it, Egil “shows the dark as well as the admirable side of the Viking ethos better than any other”. In Egil, we see a full-blooded portrait of a Viking – not sanitized, not purely heroic, but unforgettable – and through him, Egils saga invites us to view the Saga Age with all its harsh realities and enduring passions.

Chapter 4: Gísla saga – The Saga of Gísli Súrsson

A Fugitive’s Fate: The Story of Gísli Súrsson

Gísla saga Súrssonar (the Saga of Gísli Súrsson) is a shorter but no less powerful tale, often hailed as one of the greatest “outlaw sagas.” It is the tragic story of Gísli Súrsson, a man who becomes an outlaw and is pursued to the ends of the earth for a crime born of loyalty and love. Set in the Westfjords of Iceland between roughly 940 and 980 AD, the saga has the tight focus of a drama: it revolves around Gísli’s relationships with his family and closest friends, and the fatal chain of events that forces him into exile. Full of haunting dreams, intense emotions, and moral dilemmas, Gísla saga reads almost like a classical tragedy transplanted into the Viking world.

The saga’s prologue begins in Norway, providing background on Gísli’s family and a sense of fate at work. Gísli’s father is Þorbjörn Súr (“Sour”), so nicknamed after a youthful adventure when he survived a house burning by soaking hides in whey – súrr – and using them for protection. This detail gives the family its epithet “Súrsson,” and also foreshadows fire and survival as elements in Gísli’s story. Young Gísli Súrsson grows up alongside his brother Thorkell and sister Thórdís. They become entangled in feuds even before leaving Norway: Gísli avenges an insult to his sister by killing a seducer, triggering retaliation that forces the family to flee Norway in a manner similar to Egil’s family. In one dramatic episode, their enemies burn their homestead, but the Súrsson family escapes by using whey-soaked hides (the origin of the “Súr” moniker). Gísli and his kin then emigrate to Iceland, part of the settlement era wave. They journey across the sea and eventually establish a farm in Haukadalur in the Westfjords of Iceland.

In Iceland, the saga quickly introduces the tight-knit group of friends and in-laws whose fates will become tragically interwoven. Gísli and his brother Thorkell are very close. They become friends with two other men in the region: Vésteinn Vesteinsson (often anglicized Vesteyn) and Þorgrímur Þorsteinsson (Thorgrim). This quartet – Gísli, his brother Thorkell, his brother-in-law Thorgrim (who marries their sister Thórdís), and his best friend Vesteinn (who is Gísli’s wife’s brother) – are initially such good comrades that they swear an oath of blood brotherhood. In a memorable scene, they prepare to seal their friendship with a ritual: they cut a strip of turf and are to stand under it, mixing blood. But at the last moment, Thorgrim backs out of the oath, saying he cannot support Vesteinn as a brother because he has obligations to the other two already. Gísli, offended that Thorgrim won’t include Vesteinn equally, also withdraws his hand, breaking off the ceremony. This aborted oath is a turning point – a seer named Gest had foretold that within three years these men would fall into bitter discord, and indeed the failed oath seems to set destiny on its course. The saga pointedly notes that from this moment, the characters’ actions appear controlled by fate, leading them down a tragic path.

The personal relationships become further complicated by secrets and jealousy. Gísli is happily married to Auðr (Aud), a devoted and courageous woman. Thorkell (Gísli’s brother) is married to Ásgerður (Asgerd). Early on, a bit of gossip surfaces: it turns out Asgerd (Thorkell’s wife) used to be in love with Vesteinn before she married Thorkell, and similarly Aud (Gísli’s wife) was once fond of Thorgrim before Gísli courted her. When Thorkell learns of his wife’s past feelings for Vesteinn, he grows uneasy and resentful. For his part, Gísli is less troubled by Aud’s past admiration of Thorgrim – Gísli seems secure in Aud’s love. But the knowledge drives a wedge between the two brothers: Thorkell becomes brooding and decides to distance himself from Gísli. He moves out of their shared household and goes to live with his brother-in-law Thorgrim, effectively siding with Thorgrim and leaving Gísli and Vesteinn as the other pair. At this point the saga’s central conflict lines are drawn: Gísli and Vesteinn remain close friends (and brothers-in-law, since Vesteinn is Aud’s brother), while Thorkell and Thorgrim form another alliance.

Thorkell and Thorgrim, now often speaking privately, come to see Vesteinn as a threat or nuisance – partly due to the jealousies involved and partly because Vesteinn is a bold figure who might claim Aud’s attention or challenge Thorgrim’s standing. It is hinted that Thorkell and Thorgrim begin plotting something against Vesteinn. The honourable course would be to sort things out peacefully, but pride and envy prevent open dialogue.

Oblivious to the brewing danger, Vesteinn – who often travels abroad on trading ventures – decides to return to Iceland to visit Gísli. Gísli hears rumors that Thorgrim and Thorkell might mean harm to Vesteinn. Concerned, Gísli sends messengers to warn Vesteinn not to come, even giving them a token (a coin) to show the seriousness of the danger. But Vesteinn is fearless and loyal; he refuses to alter his plans, trusting his friends. Several people along the way warn him too, but he presses on, determined to reunite with Gísli and the others.

Vesteinn arrives at Gísli’s farm and is welcomed warmly by Gísli and Aud. That very night, however, disaster strikes. In the dark, as everyone sleeps, an assailant sneaks into the house and murders Vesteinn, driving a spear into him as he lies in bed. The household awakes to find Vesteinn dead. Chaos and grief ensue. Who could have done this terrible deed? The saga builds suspense here – it’s an apparent “whodunit.” Gísli is stricken but immediately takes charge of the funeral preparations. One clue emerges: the killer left the murder weapon, a spear, sticking in Vesteinn’s body. Gísli pulls it out and notices that an ornamental spearhead cover (a sheath) he had made is missing – suggesting the spear was one of a matching pair Gísli himself had crafted and given as gifts, one to Vesteinn and one to Thorgrim. This is a silent confirmation to Gísli that Thorgrim is the likely murderer (since Vesteinn wouldn’t kill himself with his own spear, the other matching spear belonged to Thorgrim).

Gísli faces a wrenching choice: Thorgrim is his brother-in-law (married to Gísli’s sister Thórdís) and was once his close friend; but Vesteinn was like a brother to him and has been treacherously killed under his roof. Honour and love demand vengeance. Gísli keeps his suspicions to himself. During Vesteinn’s wake, Thorgrim behaves rather smugly – at one point he comments that once such a killing would have been big news (implying he is jaded or guilty), and he pointedly inquires if Aud is weeping for Vesteinn (almost taunting Gísli). These hints confirm Thorgrim’s guilt in Gísli’s eyes. So, one dark night, Gísli acts: he slips over to Thorgrim’s house at Saebol and, in a swift, stealthy attack, kills Thorgrim with a spear – the deed is done so quickly that Thorgrim’s last words are, “Awake, I am wounded to death” before he collapses. Gísli escapes undetected into the darkness.

The next morning, word spreads that Thorgrim has been slain in his bed, in the same fashion as Vesteinn. Initially, no one knows who did it. Gísli publicly helps investigate and even goes to fetch Thorgrim’s body. Thorgrim’s widow (Gísli’s sister Thórdís) is shrewd and soon suspects that Gísli might be responsible – after all, he had the strongest motive. When Thórdís finds a bloody knife of Gísli’s at the murder site, she becomes certain and later reveals this to her new husband, Börkur (Bork), Thorgrim’s brother. But before that evidence comes out, Gísli nearly gets away with an honourable resolution: at Thorgrim’s funeral feast, he manages the proceedings and even composes a verse subtly hinting at his deed (saying the “spear stands bloody” at Saebol). Thorgrim’s young son also inadvertently says something that indicates Gísli’s guilt (not understanding his words). Suspicion begins to mount, and finally Thórdís openly accuses her own brother of killing her husband. This breaks the facade.

Now Gísli is in a dire position. He has committed killings within the family – he killed his sister’s husband, albeit to avenge his wife’s brother. According to Icelandic law, this is murder and there will be no easy settlement. Thorgrim’s brother Börk takes up the blood-feud. Pushed by his wife Thórdís (who, despite being Gísli’s sister, now wants justice for her slain husband), Börk and his allies bring a case against Gísli at the local assembly. Gísli does not contest what he’s done. The verdict is swift: Gísli is declared an outlaw – meaning he can be legally killed by anyone and will receive no protection from law or society. All his property is confiscated by his enemies. This sentence essentially condemns Gísli to a life on the run, cut off from family and the community.

What follows is the saga of Gísli’s outlawry, a period lasting nearly 13 years – an almost unheard-of length of time to survive as a fugitive (only the famous outlaw Grettir survived longer, as the saga notes). Gísli must rely on his wits, his courage, and above all the help of a few loyal individuals, chiefly his wife Aud. Aud chooses to stick by Gísli despite the hardship. Their bond is one of the most touching elements of the saga – Aud is portrayed as steadfast and resourceful, often saving Gísli from capture.

In the initial phase of his outlawry, Gísli hides in the area near his home. He has secret hideouts in the rugged landscape of the Westfjords – including a cave behind a waterfall and an underground lair he digs in the ground. Aud and a handful of trusted friends ferry him supplies and keep his whereabouts hidden. Gísli endures harsh winters in these shelters, always a step ahead of Börk’s search parties. Börk is determined to kill Gísli, both to avenge Thorgrim and to satisfy Thórdís. Börk enlists a notorious bounty hunter, Eyjólfur (Eyjolf the Grey), to track Gísli down, offering rich reward.

The saga intensifies as Eyjolf and his men comb the region for Gísli. Several close calls occur: once, Eyjolf nearly catches Aud at home but she cleverly deceives him about Gísli’s whereabouts. In one memorable encounter, Eyjolf comes to Aud with a bag of silver, trying to bribe her to betray her husband. The proud Aud pretends to consider it, then suddenly throws the silver at Eyjolf’s face, driving him away in humiliation. This incident shows Aud’s unwavering loyalty and courage – she literally strikes the bounty hunter rather than give up Gísli.

Throughout his fugitive years, Gísli is tormented not only by constant danger but also by strange dreams. The saga emphasizes a series of dreams in which two women visit Gísli in his sleep: one is a good dream-woman who comforts him and brings hopeful visions, the other a bad dream-woman who taunts him with images of doom. These dreams become more vivid as time passes, reflecting Gísli’s psychological state. The good dream-lady shows him pleasant scenes, perhaps of an afterlife among friends; the bad one shows him his own impending death and the futility of escape. This duality of dreams adds a layer of the uncanny and fate – it is as if supernatural figures are foretelling and accompanying Gísli’s lonely path, offering him solace and terror in equal measure. The dream motif also highlights Gísli’s internal struggle: he is a man trying to reconcile his actions (born of loyalty) with the relentless fate that those actions have unleashed.

As years wear on, many who once helped Gísli grow weary or afraid, and his circle of refuge shrinks. Eventually, Gísli is forced to flee his district entirely. He spends time hiding on a remote friend’s farm, even disguising himself as a labourer. But Eyjolf’s network of informants gradually pin him down. The saga builds to the inevitable final confrontation: Eyjolf and about a dozen men corner Gísli at Geirþjófsfjörður, a remote fjord where Gísli’s sister-in-law lives. In the saga’s climactic battle, Gísli – though all alone except for a woman (his wife’s foster-daughter who tries to help) – makes a legendary last stand similar to Gunnar’s stand in Njál’s saga, but perhaps even more poignant given his long suffering.

On that fateful day, Gísli is outnumbered by Eyjolf’s crew. Though he is weary from years of flight, Gísli fights like a hero out of myth. He is described leaping and dodging on the hillside, killing several of his attackers with sword and spear. Aud and their foster-daughter Guðríðr even join the fray briefly – Aud strikes one of the attackers with a club to aid her husband. Gísli manages to slay around eight of the men, including some of Eyjolf’s best fighters. He himself sustains a grave leg wound that slows him down. Finally, exhausted and bleeding, Gísli backs against a rock and faces Eyjolf and the last of his men. In a final burst, Gísli hurls his spear and kills one more foe, but Eyjolf and the remaining two rush him. Gísli falls, killed after a fierce struggle. In dying, he chants his final verse – proudly declaring he has made a good fight and that “no one will be a stout-hearted braver man” than he in such circumstances (according to some versions). Thus ends Gísli’s life, in brave combat, undefeated in spirit even as his body fails.

The aftermath is both grim and consoling. Eyjolf has paid a high price, losing many men, but he has the outlaw’s head to claim his reward. However, the saga doesn’t conclude with the triumph of the bounty hunters. It gives us closure for the survivors: Gísli’s beloved wife Aud, who has lost everything, refuses to stay in Iceland under Börk’s power. Aud is offered money by Eyjolf (again) after Gísli’s death – this time the blood money for her husband – and she spurns it. She and Gísli’s foster-daughter Gudrid manage to escape and eventually leave Iceland entirely. The saga mentions that Aud goes abroad, converts to Christianity, and even makes a pilgrimage to Rome, never returning to Iceland. This detail is telling: it suggests Aud seeking a form of spiritual solace and a world far removed from the violent pagan one that destroyed her family. Meanwhile, Thórdís (Gísli’s sister, who had prompted her husband Börk’s vengeance) comes to regret her role. In one version of the saga, she is so angered by Eyjolf’s shameful tactics (the attempted bribery of Aud) that she later kills Eyjolf in revenge – thus avenging Gísli indirectly and ending the blood feud on her own terms. Thórdís then divorces Börk and leaves Iceland as well.

In the end, virtually none of the principal characters remain in their homeland – a sign of how destructive the feud has been. Gísli is remembered as an honourable man who met a cruel fate because he chose loyalty over law. The saga’s closing words often emphasize how “all men agreed Gísli had been the most righteous outlaw” or that he was a man of great integrity unjustly hounded. Indeed, one character in the saga earlier had remarked that Gísli “would be the most honourable man in the land, if only he could be a law-abiding man” – implying that it was circumstance, not evil intent, that made him an outlaw.

Themes and Analysis

Gísla saga is sometimes described as having the feel of a domestic tragedy set in the Viking age. One of its foremost themes is fidelity to loved ones versus the demands of society’s law. Gísli is fundamentally a man who chooses the unwritten code of loyalty over the formal code of law. When he kills Thorgrim to avenge Vesteinn, he knows he is breaking the law; yet in the ethical world of the saga, readers sympathize with Gísli because his motive is noble – he is avenging a wrongful murder of his dear friend and brother-in-law. This tension between personal honour and legal justice drives the saga. Icelandic society cannot accommodate such a killing, no matter the motive, so Gísli is cast out. The saga thereby invites the reader to question the fairness of the law: Gísli’s act of vengeance, though illegal, is portrayed as an act of loyalty and necessity. The harsh outlaw fate imposed on him feels unjust, highlighting a gap between legal guilt and moral innocence. In this way, Gísla saga clearly opposes the cycle of violence, even as it shows how that cycle is fueled by the culture of honour. The saga’s heart lies in the conflict of loyalties: Gísli is torn between loyalties to different family members (sister vs wife vs friend), and whichever choice he makes will lead to tragedy. His story demonstrates the cruel dilemma that the old honour code can impose.

Another prominent theme is fate versus free will. Once the blood-brotherhood oath fails and the prophecy of betrayal is uttered, the saga takes on an air of inevitability. Characters seem unable to escape what has been foretold. Despite Gísli’s attempts to warn Vesteinn, Vesteinn comes to his doom. Despite all of Gísli’s ingenuity and endurance in hiding, the net closes around him as if destiny will have its due. The recurring dreams reinforce this fatalism – Gísli’s good and bad dream-women essentially narrate his fate, and Gísli is powerless to change the outcome they hint at. This use of dreams and omens is common in sagas, but Gísla saga particularly integrates them into the emotional arc of the story. The dreams provide comfort and terror, almost like manifestations of Gísli’s hopes and fears. One could interpret the good dream-woman as symbolizing Gísli’s clear conscience and the promise of peace in the next life (she often appears when he refuses to give up or when he reconciles with his fate), whereas the bad dream-woman represents the inescapable doom shadowing him. The tension between these dreams adds a psychological depth to the saga unusual for this literature; it externalizes Gísli’s internal struggle to maintain hope under relentless pressure. In a way, the saga suggests that while fate is inexorable, the human spirit (embodied by the good dream-lady’s encouragement) can still find dignity and meaning in resisting it to the end.

The theme of “conflicting loyalties” is explicitly highlighted by many readers of Gísla saga. Gísli’s tragedy is that he cannot satisfy all the demands of loyalty: he avenges one kinsman (Vesteinn) but in doing so, he betrays another (his sister’s husband Thorgrim). The saga makes it easy to empathize with Gísli because he consistently acts out of a sense of duty to those he loves. Even his initial killing of Bard in Norway (the seducer of his sister) was motivated by protecting family honour. The saga poses the question: what happens when doing the right thing for one loved one makes you a criminal to others? The answer it provides is the sorrowful tale of Gísli’s isolation. There is a strong undercurrent of emotional intensity in this saga – scholars often note it shows “far less emotional restraint than is usual in the sagas”. Characters openly weep, passionately declare loyalty or hatred, and the narrative invites us to feel the weight of their decisions. Aud’s unwavering support, Thórdís’s fury and later remorse, Thorkell’s jealousy, and Gísli’s own tears for Vesteinn all contribute to a tone that is at times raw with feeling. This emotional frankness makes Gísla saga particularly engaging; it’s easy to imagine the fear, anger, and love that drive each step of the story.

The saga also has a moral or ethical dimension that might reflect its 13th-century Christian authorship. Although the saga’s events are set in pagan times (Christianity has not yet been adopted in Iceland during Gísli’s life), the narrative voice seems to disapprove of needless violence and treachery. The “bad guys” in the saga are those who lack honour: e.g., Eyjolf, who resorts to bribing women and acts purely for money; or Thorgrim and Thorkell, who murder covertly and out of envy. By contrast, Gísli is consistently honourable (within the code of vengeance) and Aud is virtuous and faithful. The saga clearly sides with Gísli and Aud. In the end, Aud’s conversion to Christianity and journey to Rome can be seen as a statement that the saga’s values align with a more Christian idea of righteousness rather than the old cycle of revenge. Some have argued the saga was written to show that even in the pagan past, there were those who followed a kind of innate “natural Christianity” of goodness – Gísli being an example of a man who, though pagan, behaves with a kind of saintly loyalty and suffers innocently, and Aud practically is a Christian in her mercy and steadfastness. While the saga doesn’t explicitly preach, the fates it deals out speak volumes: the schemers (Thorgrim, Thorkell) and violent men for hire (Eyjolf) meet bad ends or are morally condemned, whereas Aud, who stands for love and fidelity, survives and finds a new peaceful life under a new faith.

Structure and style: Gísla saga is tightly plotted, with a clear beginning (the buildup of relationships and conflict), middle (the outlaw life, with rising tension), and end (the final fight and aftermath). It’s often praised as one of the best-constructed sagas for this reason – nothing in it feels superfluous. It also skillfully uses narrative devices: the aborted oath sets the stage, the matching spear and verse clues create a subtle mystery, the dreams provide internal continuity. The saga often juxtaposes scenes to draw ironic contrasts: for example, Vesteinn’s murder night and Thorgrim’s murder night echo each other, as do the two funeral feasts (for Vesteinn and Thorgrim) where insinuations fly. This mirroring amplifies the sense of fate and poetic justice.

Another notable aspect is the role of women in Gísla saga. Women drive significant parts of the plot. Thórdís’s actions (her affair, then her later revelation of Gísli’s guilt) directly influence outcomes. Most importantly, Aud stands out as one of the strongest female figures in the sagas. Not only does she protect Gísli with daring and cleverness, but she also physically participates in his defense (striking Eyjolf, and in some versions, killing a man in the final fight as well). The saga portrays her as brave, intelligent, and morally upright. In a time when many saga women are either instigators of strife (like Hallgerd in Njál’s saga) or passive figures, Aud is refreshingly heroic and sympathetic. The partnership of Aud and Gísli is at the emotional center of the saga – their scenes together, whether it’s planning hiding spots or saying goodbye before the last battle, are filled with mutual respect and love. This emphasis on a strong marital love is somewhat unique among the sagas and gives Gísla saga a poignant depth. It underscores the theme of loyalty: Aud’s loyalty to Gísli equals Gísli’s loyalty to Vesteinn, making Aud a mirror of Gísli’s best qualities.

In terms of legacy, Gísla saga is often appreciated for its dramatic and accessible storytelling. For general readers, it offers a compact saga that still delivers the quintessential elements: feuds, fights, an outlaw’s adventures, and supernatural omens. Modern audiences might particularly enjoy the almost cinematic quality of Gísli’s chase and the pathos of his personal struggle. The saga’s scenery – the remote Westfjords – also contributes to the mood: the landscape is depicted as stark and unforgiving, a fitting stage for Gísli’s lone wanderings. Because the saga survives in multiple versions (some longer, some shorter), it’s clear it was a popular tale that scribes revisited. Britannica succinctly calls it the story of “an outlaw poet… who was punished by his enemies for loyally avenging his foster brother” – indeed, Gísli is an outlaw and a bit of a poet (he composes a few moving stanzas, especially in his last moments, though his poetic output is smaller than Egil’s or Gunnarr’s). The idea of the “outlaw poet” further cements the notion that sagas often admire characters who, while on the wrong side of the law, uphold deeper virtues.

In conclusion, Gísla saga presents a heartrending narrative of a good man caught in bad circumstances. Its themes of honour, loyalty, and fate are delivered in a highly engaging prose style with strong characterization and emotional resonance. Gísli’s fate evokes the pity and fear of classic tragedy – we sense it coming, we understand why it happens, and we mourn it when it does. The saga invites readers to contemplate the price of vengeance and the value of fidelity. Even stripped of its historical context, it stands as an engrossing human story: a brother betrayed, a friend avenged, a life sacrificed, and a love that endures beyond death. In the canon of Icelandic sagas, Gísla saga may be shorter in length than Njál’s saga, and narrower in scope than Egil’s saga, but it is every bit as rich in meaning and memorability. It leaves us with the image of Gísli, standing wounded but defiant on a stony Icelandic hillside, fighting for what he loved until he could fight no more – an image that encapsulates the saga’s enduring appeal.

Leave a Reply